Part 1: DIY debugger in Golang

The first thing I do when I create a project is to create the debugger launch config at the .vscode folder. Debuggers help me to avoid putting print statements and building the program again. I always wondered how a debugger can stop the program on the line number I want and be able to inspect variables. Debugger workings have always been dark magic for me. At last, I managed to learn dark art by reading several articles and groking the source code of delve.

In this post, I’ll talk about my learning while demystifying the dark art of debugger.

Problem statement

Let’s define the problem statement before coding. I have a sample golang program that prints random ints every second. The goal which I want to achieve is that our debugger program should print breakpoint hit before our sample program prints the random integer.

Here is the sample program which prints random ints at every second.

1. package main

2.

3. import (

4. "fmt"

5. "math/rand"

6. "time"

7. )

8.

9. func main() {

10. for {

11. variableToTrace := rand.Int()

12. fmt.Println(variableToTrace)

13. time.Sleep(time.Second)

14. }

15. }

16.

Solution

Now that we know what we want to achieve. Let’s go step by step and solve the problem statement.

The first step is to pause the sample program before it prints the random int. That means we have to set the breakpoint at line number 11.

To set the breakpoint at line number 11, we must gather the address of instruction at line number 11.

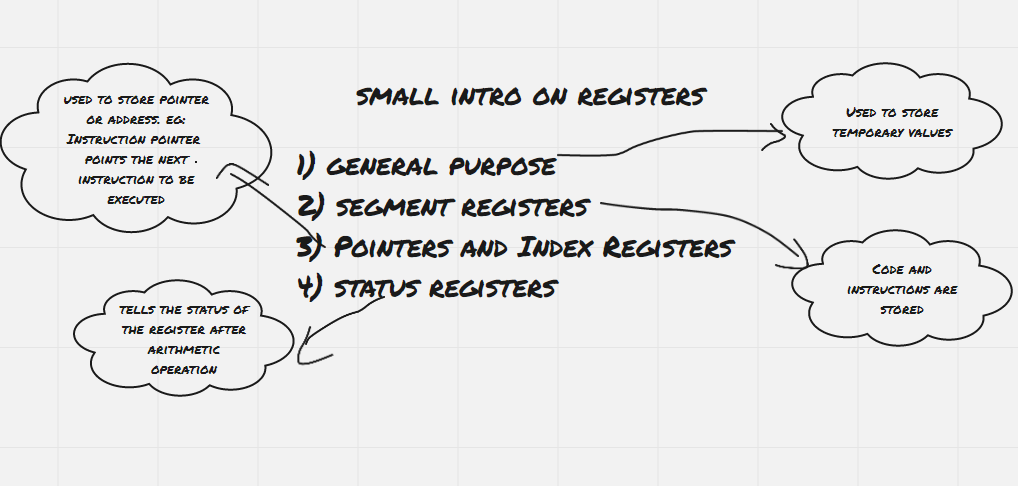

Some of us know from high school that all high-level language is converted into assembly language at the end. So, how do we find the address of the instruction in the assembly language?

Luckily, compilers add debug information along with the optimized assembly instruction on the output binary. Debug information contains information related to the mapping of assembly code to high-level language. For Linux binaries, debug information is usually encoded in the DWARF format.

DWARF is a debugging file format used by many compilers and debuggers to support source level debugging. It addresses the requirements of a number of procedural languages, such as C, C++, and Fortran, and is designed to be extensible to other languages. DWARF is architecture independent and applicable to any processor or operating system. It is widely used on Unix, Linux and other operating systems, as well as in stand-alone environments. source: http://www.dwarfstd.org/

DWARF format can be parsed using objdump tool.

The below command will output all the addresses of the instruction and it’s mapping to the line number and file name.

objdump --dwarf=decodedline ./sample

objdump command will output similar to this:

File name Line number Starting address View Stmt

/home/poonai/debugger-example/sample.go:

sample.go 9 0x498200 x

sample.go 9 0x498213 x

sample.go 10 0x498221 x

sample.go 11 0x498223 x

sample.go 11 0x498225

sample.go 12 0x498233 x

sample.go 12 0x498236

sample.go 13 0x4982be x

sample.go 13 0x4982cb

sample.go 11 0x4982cd x

sample.go 12 0x4982d2

sample.go 9 0x4982d9 x

sample.go 9 0x4982de

sample.go 9 0x4982e0 x

sample.go 9 0x4982e5 x

The output clearly states that 0x498223 is the starting address of line number 11 for sample.go file.

The next step is to pause the program at the address 0x498223

Trick to pause the program execution

CPU will interrupt the program whenever it sees data int 3. So, we just have to rewrite the data at the address 0x498223 with the data []byte{0xcc} to pause the program.

In computing and operating systems, a trap, also known as an exception or a fault, is typically a type of synchronous interrupt caused by an exceptional condition (e.g., breakpoint, division by zero, invalid memory access). source: wikipedia

Does that mean we have to rewrite the binary at 0x498223? No, we can write it using ptrace.

Ptrace to rescue

ptrace is a system call found in Unix and several Unix-like operating systems. By using ptrace (the name is an abbreviation of “process trace”) one process can control another, enabling the controller to inspect and manipulate the internal state of its target. ptrace is used by debuggers and other code-analysis tools, mostly as aids to software development. source:wikipedia

ptrace is a syscall that allows us to rewrite the registers and write the data at the given address.

Now we know which address to pause and how to find the memory representing lines, and manipulate the memory of the sample program. So, let’s put all this knowledge into action.

exec a process by setting Ptrace flag to true, so that we can use ptrace on the execed process.

process := exec.Command("./sample")

process.SysProcAttr = &syscall.SysProcAttr{Ptrace: true, Setpgid: true,

Foreground: false}

process.Stdout = os.Stdout

if err := process.Start(); err != nil {

panic(err)

}

The breakpoint can be set at 0x498223 by replacing the original data with int 3 (0xCC). This can be done by PtracePokeData.

func setBreakpoint(pid int, addr uintptr) []byte {

data := make([]byte, 1)

if _, err := unix.PtracePeekData(pid, addr, data); err != nil {

panic(err)

}

if _, err := unix.PtracePokeData(pid, addr, []byte{0xCC}); err != nil {

panic(err)

}

return data

}

You must already be wondering why there is PtracePeekData, other than PtracePokeData. PtracePeekData allows us to read the memory at the given address. I’ll explain later why I’m reading the data at the address 0x498223.

Since we set the breakpoint we’ll continue the program and wait for the interrupt to happen. This can be done by PtraceCont and Wait4

if err := unix.PtraceCont(pid, 0); err != nil {

panic(err.Error())

}

// wait for the interupt to come.

var status unix.WaitStatus

if _, err := unix.Wait4(pid, &status, 0, nil); err != nil {

panic(err.Error())

}

fmt.Println("breakpoint hit")

After the breakpoint hits, we need the program to continue as usual. Since we already modified the data at 0x498223 the program doesn’t run as usual. So we need to replace the int 3 with original data.

Remember, we captured the original data at 0x498223 using PtracePeekData while setting the breakpoint. Let’s just revert to the original data at 0x498223.

if _, err := unix.PtracePokeData(pid, addr, data); err != nil {

panic(err.Error())

}

Just reverting to original data doesn’t run the program as usual. Because the instruction at 0x498223 is already executed when breakpoint hits.

So, we want to tell the CPU to execute the instruction again at 0x498223.

CPU executes the instruction that the instruction pointer points to. If you have studied microprocessors at university, you might remember.

0x498223 then the CPU will execute the instruction at 0x498223 again.CPU registers can be manipulated usingPtraceGetRegs and PtraceSetRegs.

regs := &unix.PtraceRegs{}

if err := unix.PtraceGetRegs(pid, regs); err != nil {

panic(err)

}

regs.Rip = uint64(addr)

if err := unix.PtraceSetRegs(pid, regs); err != nil {

panic(err)

}

Now that we modified the register, if we continue the program then it’ll execute the normal flow. But we want to hit the breakpoint again, so we’ll tell the ptrace to execute only the next instruction and set the breakpoint again. PtraceSingleStep allows us to execute only one instruction.

func resetBreakpoint(pid int, addr uintptr, originaldata []byte) {

// revert back to original data

if _, err := unix.PtracePokeData(pid, addr, originaldata); err != nil {

panic(err.Error())

}

// set the instruction pointer to execute the instruction again

regs := &unix.PtraceRegs{}

if err := unix.PtraceGetRegs(pid, regs); err != nil {

panic(err)

}

regs.Rip = uint64(addr)

if err := unix.PtraceSetRegs(pid, regs); err != nil {

panic(err)

}

if err := unix.PtraceSingleStep(pid); err != nil {

panic(err)

}

// wait for it's execution and set the breakpoint again

var status unix.WaitStatus

if _, err := unix.Wait4(pid, &status, 0, nil); err != nil {

panic(err.Error())

}

setBreakpoint(pid, addr)

}

So far we have learned how to manipulate registers and set breakpoints. Let’s put all these into a for loop and drive the program.

pid := process.Process.Pid

data := setBreakpoint(pid, 0x498223)

for {

if err := unix.PtraceCont(pid, 0); err != nil {

panic(err.Error())

}

// wait for the interrupt to come.

var status unix.WaitStatus

if _, err := unix.Wait4(pid, &status, 0, nil); err != nil {

panic(err.Error())

}

fmt.Println("breakpoint hit")

// reset the breakpoint

resetBreakpoint(pid, 0x498223, data)

}

Phew, Finally we able to print breakpoint hit before our sample program prints random int.

breakpoint hit

6129484611666145821

breakpoint hit

4037200794235010051

breakpoint hit

3916589616287113937

breakpoint hit

6334824724549167320

breakpoint hit

605394647632969758

breakpoint hit

1443635317331776148

breakpoint hit

894385949183117216

You can find the full source code at https://github.com/poonai/debugger-example

That’s all for now. Hope you folks learned something new. In the next post, I’ll write how to extract values from the variables by reading DWARF info. You can follow me on Twitter to get notified about part 2.